stardust express, April '25

on Accessibility, part 1; beginning reflection on what I've learned attending the Multiplié dansfestival Trondheim 2025.

if i wasn’t as smart as i am, i’d have probably sat down today and tried to achieve coherence.

truthfully, that’s exactly what i did… by which i don’t mean to imply that i’m the opposite of smart, no. the opposite of smart—which isn’t stupid—would look past their fear of inconsistency and inelegance, would force themselves and their experiences into language they’re unable to make sense of, and—having exhausted themselves trying—would end the day by hitting the delete button.

[i’m not just speculating here, i’m speaking from experience.]

defined by the oxford dictionary of english as the inability to think clearly, stupid must be what one becomes under the condition of exhaustion. which means that in case of stupidity exhaustion must come first and begs the question, where does exhaustion come from?

the opposite of smart is intentionally ignorant. this is not someone who’s lacking perspective, but someone who is intentionally refusing to acquire it—for whatever reason (cough: fear). it is the intentionally ignorant who looks past their fear of inconsistency and inelegance on purpose, forces themselves and their experiences into language they’re unable to make sense of on purpose, and—having exhausted themselves into stupidity—ends the day by hitting the delete button on purpose. and beating themselves about it late into the night. on purpose.

but why would anybody do anything like that on purpose? why would anybody prefer to stay on the same course, the familiar course, the one sara ahmed calls ‘the path well trodden’, instead of taking the risk and stepping off the beaten path? martin hagglund examines this phenomenon via incorrigible propositions. BMC speaks on this topic, too.

[should i expand? would you continue reading?]

whatever life is these days, coherent it is not.

for whatever reason, i am terrified of incoherency.

alas, i will not look for it.

i’m stepping off the beaten path.

sara ahmed, lead the way!

for whatever reason? here’s a reason.

whenever i used to wake up at the same time every day, go to rehearsal, and navigate constant social tensions with folks that i (strictly speaking) did not choose to work with, i used to be able to say that i was a dancer and appear clearly in other people’s imaginaries. i hate to admit it, but in being able to clarify my image with a word i experienced relief. i was so hungry for the experience of this specific type of relief that i’d prioritise experiencing it by associating myself with the word even when the word i was associating myself with felt wrong, or when the clarity of my image in another’s imaginary felt inconsistent with my lived experience.

on occasion, i considered distancing myself from the word—e.g., by quitting my job—but then i’d get another contract, which guaranteed to extend my access to social security; wage, pension, and health insurance, thereby making it possible for me to continue engaging in my favourite activity; supporting my community pro bono. talking about a life worth living. notes on gift economy.

then the pandemic came, and changed everything.

and then i got diagnosed with ADHD—because i had access to a wage, and health insurance—and everything changed again.

accessibility

You don’t know you’re not being considered until someone considers you. And your needs.

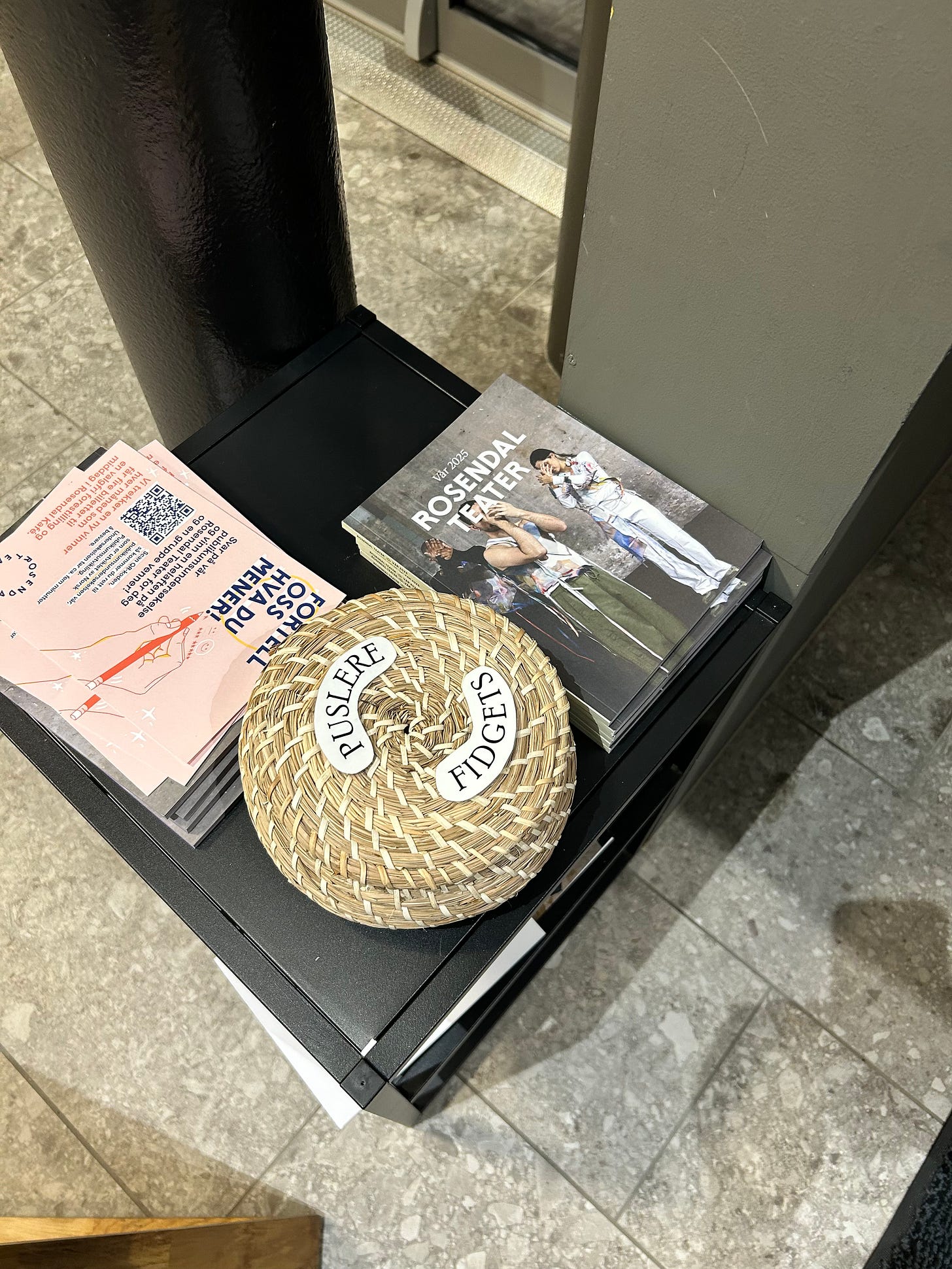

— posted in trondheim, on an instagram story across the image featured below

masking recognises that, to meet social expectations and blend into society, neurodivergent folk need to act intentionally where their neurotypical counterparts can afford to act spontaneously. masking is what neurodivergent folk do to avoid bullying and discrimination, hide discomfort in environments that are not accessible to them, make and maintain friendships and relationships, and improve employment opportunities and keep jobs.1

as a person who spent most of their life masking2, i experience myself in my learning that i have access needs as terrifyingly inconsistent. [i used to be okay with this. i am not okay with this. why am i not okay with this anymore?] learning that i have access needs is how i’m learning that i’m ashamed of myself and my needs, and (!) that i find it much easier to mask the fact of my having needs than acknowledge them and learn how to communicate (around) them. communicating my needs, on occasion, makes me feel downright nauseous. i am scared of being perceived as intentionally difficult, as if i’m trying to make things complicated for other people.

as if communicating one’s access needs is ever about other people. but it is, most frequently that’s exactly what it is.

my disease with my own acknowledgement of my own access needs, i think, says a lot about the status of disability in the West. were it not for my diagnosis and the years i’ve spent in therapy, i may never have gotten the chance to discover that i’ve successfully internalised a selection of discriminatory3 views and values common in the West; including but not limited to the view of disability as something that is out of the ordinary, as something that creates problems, as something that is about disabled individuals as opposed to being about the errors embedded within the procedures of the institutions we’ve made for ourselves.

“When you expose a problem you pose a problem. It might then be assumed that the problem would go away if you would just stop talking about it or if you went away.”

― Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life4

it took a humble basket containing a small number of fidget toys placed discretely by the entrance to the Rosendal Teater during the Multiplé festival5 to completely disorient my sense of self. how can the acknowledgement of my presence—in its complexity—be so discreet, yet so effective? how can a small thing like a humble basket make me feel welcome? i thought of Liz Lemon in that moment high-fiving a million angels.

the sensationally textured, bright yellow stress ball—my third favourite colour, by the way—that i found in the basked helped reduce my social anxiety and support me through the lengthy performance. but any fidget toy would have done that, my own included. what my own fidget toy can’t have done is communicate that a person like me is expected to enter this space. a person who is likely to have forgotten their fidget toy at home. not to worry, the ball in its based seemed to have been telling me, we’re ready for you. help yourself and know that you don’t have to hide.

to be continued…

https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/behaviour/masking#:~:text=Masking%20is%20described%20as%20making,and%20other%20mental%20health%20issues.

most neurodivergent folk who got diagnosed in adulthood will have adopted masking mannerisms early on in life in response to negative experiences. colloquially, we refer to those folk as high functioning. what makes a neurodivergent high functioning is the fact they managed to hide their neurodivergence into adulthood, often at the expense of their well-being. many high functioning neurodivergent folk will not have been aware of masking before getting diagnosed. [this footnote could become its own chapter.]

do all internalised discriminatory views operate in the same way? in examining my experience of my internalised discriminatory views on disability i am reminded of the experience i’d had when i was first faced with internalised homophobia.

Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 35.

https://dansit.no/multiplie-dansefestival/